Coal ash–polluted lakes are in

residential and recreational areas, invoking concern for the health of local

residents and ecosystems.

By Kimberly

M. S. Cartier14 October 2022

Credit:

alexanderuhrin/Adobe Stock

Credit:

alexanderuhrin/Adobe Stock

Sediment

cores taken from five lakes in North Carolina reveal the state’s history of

coal ash pollution from power plants. Analysis of these cores, published in Environmental

Science and Technology, explains that although coal ash deposition has

declined in recent years, its legacy lives on in the contaminants the ash left

behind to seep into the environment. These toxins could be affecting the health

of local residents and ecosystems.

“It looks very pristine and beautiful, but if you dig in, you

find piles of toxic coal ash.”

“These

are recreational lakes,” Zhen Wang, an environmental geochemistry

doctoral student at Duke University in Durham, N.C., and the lead author of the

study, said in a statement. “Some of

them…were originally built for the coal plant, but over the years, it has

become very desirable real estate where people build their dream homes. It

looks very pristine and beautiful, but if you dig in, you find piles of toxic

coal ash.”

Decades of Pollution

Coal ash is the by-product of burning

coal and is one of the most prevalent forms of industrial waste in the United

States—around 130 million metric tons are

produced every year. Ash contains toxic metals, including lead, mercury,

arsenic, and selenium, which can cause respiratory diseases and cancers

after short- or long-term exposure.

Coauthor Avner Vengosh of Duke University and his

colleagues have been investigating the water quality of lakes and groundwater

across North Carolina for more than a decade. Some of their past work has

focused on pollution in the five artificial lakes sampled in the new study—Hyco

Lake, Mayo Lake, Belews Lake, Mountain Island Lake, and Lake Sutton—each of

which is located near a coal plant.

The

team collected cores up to 70 centimeters deep from the lakes between July 2020

and August 2021. They also collected a core from Lake Waccamaw, a natural lake

close to Lake Sutton, for comparison. “The oldest sediments we collected were

aged to mid-1950s,” Vengosh said, “representing 60–70 years of sedimentation.”

Some of the cores look back to before the nearby coal plants were installed and

provide a good baseline to understand a plant’s environmental impact. For each

core, the researchers analyzed the morphology, magnetic and geochemical

properties, and strontium isotopes of the lake sediments and the embedded coal

ash to track the history of ash deposition into the lakes.

The

cores revealed three distinct phases of coal ash release into the lakes. The

first phase, from the 1960s to 1970s, saw significant deposition of both coarse

and fine-grained ash particles as ash was dumped right into the lakes. During

the second phase, from the 1970s to 1990s, the enactment of the Clean Air Act

meant that coal ash was stored in ponds next to the plant. The level of

pollution into the nearby lakes decreased during this time, and larger

particles were captured by air filters instead of entering the environment. The

third phase, from the 1990s to the present, also saw a decrease in the quantity

of coal ash deposited into the lakes as storage changed from wet coal ash ponds

to dry landfills and a few plants shifted from coal to natural gas for energy

production.

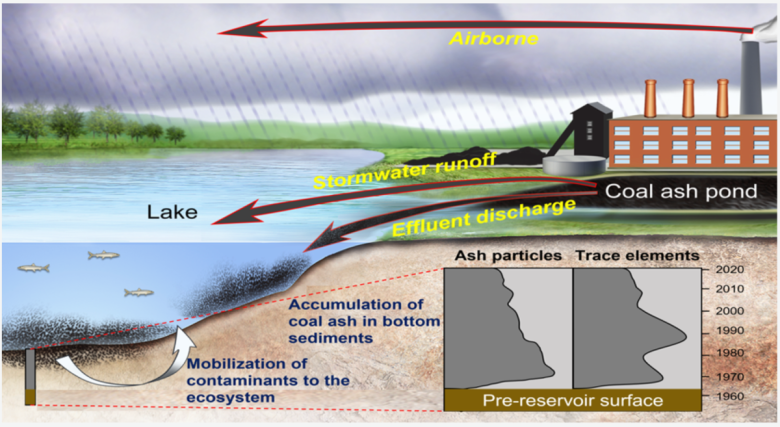

Using

streamflow data from the U.S. Geological Survey, the team found that the lakes

accumulated more coal ash during times of high streamflow and precipitation.

This result suggests that stormwater runoff, flooding, and effluent discharge

from coal ash ponds and dry landfills are some of the main mechanisms by which

the ash enters nearby lakes. Ash can also enter the air, land in the

surrounding landscape, and be washed into the lakes by rain. The researchers

noted that climate change continues to heighten the severity of the storms

striking North Carolina, including hurricanes like Florence in 2018, which

bodes ill for the coal ash still stored at these plants.

Research

speculates that coal ash enters North Carolina lakes via three pathways:

airborne ash that settles into the lakes and surrounding landscape, stormwater

runoff from coal ash ponds, and effluent discharge from coal ash ponds. Once in

the lake bottom sediments, the coal ash can release contaminants into the

water, increasing their bioavailability. Credit: Wang et al., 2022, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c04717

Research

speculates that coal ash enters North Carolina lakes via three pathways:

airborne ash that settles into the lakes and surrounding landscape, stormwater

runoff from coal ash ponds, and effluent discharge from coal ash ponds. Once in

the lake bottom sediments, the coal ash can release contaminants into the

water, increasing their bioavailability. Credit: Wang et al., 2022, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c04717

A Toxic Legacy

“The problem of coal ash legacy did not go away by switching to

natural gas.”

The

plants near Hyco, Mayo, and Belews Lakes continue to burn coal for power; the

Sutton Plant has switched to natural gas, and the Riverbend Plant near Mountain

Island Lake has been retired. But the toxic legacy of all of these energy

plants continues. “Coal ash that was stored in the nearby coal ash ponds seems

to continue [to be] displaced and transported into the lakes, specifically

during times of major flooding like hurricane episodes,” Vengosh said. “The

problem of coal ash legacy did not go away by switching to natural gas.”

Once

in the lake bed, the coal ash breaks down and releases contaminants into the water.

Those contaminants become bioavailable, which is a concern for the local

ecosystems and the residents who live nearby. All five lakes are destinations

for recreational boating, fishing, and camping, and Hyco Lake is also a

residential area.

What’s

more, Mountain Island Lake is a local drinking water intake, noted Amanda

Strawderman, polluter accountability program director for the nonprofit Clean

Water for North Carolina. This study raises pressing questions, she

said. “To what degree could suspended particles of coal ash be taken into the

municipal drinking water treatment system? Is this water being tested and

remediated for toxic coal ash constituents? If remediation is taking place, to

what extent are those 800,000 residents of the Charlotte/Mecklenburg area

bearing the cost burden of that remediation through water rates?”

“The assembly of contaminants in coal ash are highly toxic.”

This

study examined the environmental risks of

bioaccumulation of coal ash pollutants, Vengosh said, but “it is well known

that the assembly of contaminants in coal ash are highly toxic [to people].

There are reports that many

workers who participated in the cleanup of the coal ash spill in the Tennessee Valley Authority [in

2008] became severely sick, with a

high percentage of cancer. Many of them

have already passed.”

“This

alarming study reinforces the need to regulate generation and management of

coal ash waste to understand where coal ash exists,” Strawderman added, “and

strengthen protections for communities in North Carolina and beyond.”

—Kimberly

M. S. Cartier (@AstroKimCartier), Staff Writer

Citation: Cartier, K. M. S. (2022), Lake sediments record

North Carolina’s coal legacy, Eos, 103, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EO220491.

Published on 14 October 2022.

(Source: https://eos.org/articles/lake-sediments-record-north-carolinas-coal-legacy)