·

This article was first

published in April 2019 and updated in June 2022.

·

Demand for sand mining has tripled in the past two decades,

reaching 50 billion tonnes a year in 2019.

·

The UNEP says urgent action is needed to avoid a 'sand crisis'

in its Sand and Sustainability report.

·

It outlines 10 recommendations to balance the demands of the

construction industry and the need to protect the environment.

Cities are,

quite literally, built on sand. As global urbanization continues apace, the

demand for concrete, glass and construction materials that use sand increases.

By 2100, it’s

projected that up to 85% of the world’s population

will be living in cities.

But to house

those people, industrial sand mining or aggregate extraction – where sand and

gravel are removed from river beds, lakes, the oceans and beaches for use in

construction – is happening at a rate faster than the materials can be renewed,

which is having a huge impact on the environment.

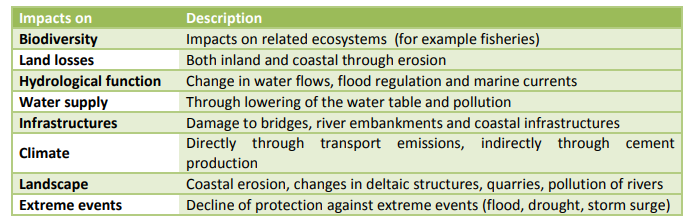

The

environmental impacts of sand mining. Image: UNEP

How much sand

is being mined?

Sand

'resources' (including gravel and crushed stone) are the second most exploited natural

resource in the world after water.

Sand mining has

tripled in the past two decades, with demand reaching 50 billion tonnes a year

in 2019, according to the latest report from the UN Environment Programme

(UNEP).

In 2012 alone,

the UNEP estimates enough concrete was created to build

a wall around the equator measuring 27 metres high by 27 metres

wide.

But extraction,

sourcing, use and management of sand is unregulated in many parts of the world,

says the UNEP, which means we are consuming it faster than it can be replaced

by geological processes.

Urgent action

is needed to avert a "sand crisis", including a ban on beach

extraction, the Sand and Sustainability report said.

The environmental

impact of sand mining

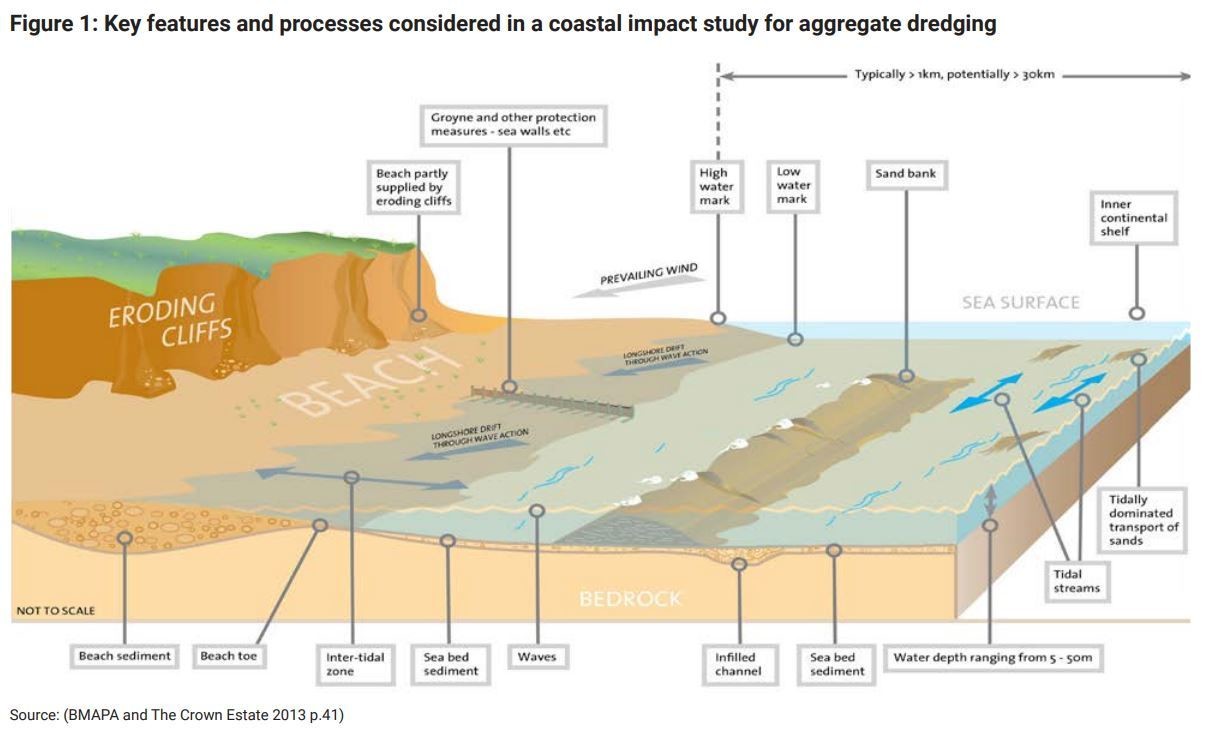

Coastal

features that could be affected by sand and gravel mining. Image: UNEP

Sand minimg

from rivers and marine ecosystems, leads to "significant environmental

impacts, including coastal and river erosion, shrinking deltas, land-use

changes, air pollution, salinization of coastal aquifers and groundwater

reserves, threats to freshwater and marine fisheries and biodiversity,"

says the UNEP.

In 2018, the

World Wildlife Fund (WWF) warned that sand mining of river deltas, such as the

Yangtze and Mekong, is increasing the risk of

climate-related disasters, because there’s not enough sediment to

protect against flooding.

“Keeping sand

in the rivers is the best adaptation to climate change,” the WWF’s Marc Goichot

told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. “If a river delta receives enough

sediment, it builds itself above sea level in a natural reaction.”

In 2020, the last coastal sand mine in the US

closed in Monterey Bay, following protests from

environmentalists over the erosion of California’s beaches.

What can be

done to avoid a sand crisis?

While pressure

on governments to regulate sand mining is increasing, more needs to be done to

find alternatives for use in construction and for solving the world’s

continuing housing crises.

The UNEP report

outlines 10 recommendations for averting a sand crisis, which would balance the

demands of the construction industry and the protection of the environment:

How the UNEP says we can avoid a sand

crisis. Image: UNEP

In its 2014

report, Sand, Rarer Than One Thinks,

the UNEP Global Environment Alert Service suggested optimizing the use of

existing buildings and infrastructure, as well as using recycled concrete

rubble and quarry dust instead of sand.

Breaking the

reliance on concrete as the go-to material for building houses, by increasing

the tax on aggregate extraction, training architects and engineers, and looking

to alternative materials such as wood and straw, would also reduce our demand

for sand mining.

(Source: FUTURE OF THE ENVIRONMENT, https://www.weforum.org/ )